A desire was restlessly turning over in me but it wasn’t until I woke on Tuesday to a half-remembered poem gnawing away the ecotones of sleep that something started to take shape. The poem is called “Tear it Down” by Jack Gilbert:

We find out the heart only by dismantling what

the heart knows. By redefining the morning,

we find a morning that comes just after darkness.

We can break through marriage into marriage.

By insisting on love, we spoil it, get beyond

affection and wade mouth-deep into love.

We must unlearn the constellations to see the stars.

But going back toward childhood will not help.

The village is not better than Pittsburgh.

Only Pittsburgh is more than Pittsburgh.

Rome is better than Rome in the same way the sound

of raccoon tongues licking the inside walls

of the steel garbage tub is more than the stir

of them in the muck of garbage. Love is not

enough. We die and are put into the earth forever.

We should insist while there is time. We must eat

through the wildness of her sweet body already

in our bed to reach the body within that body.

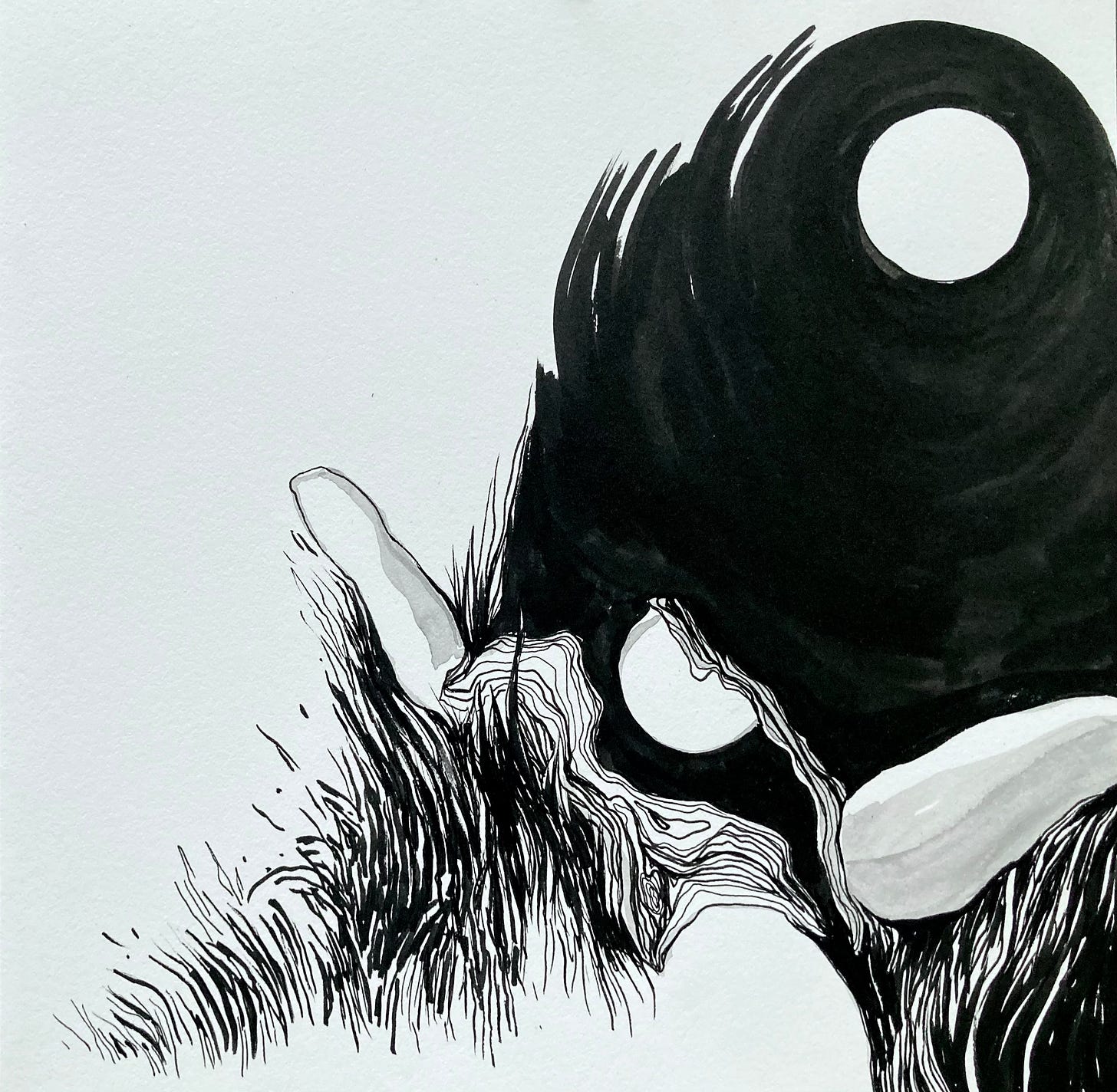

Why this poem, for a substack focused on the ecologies of creativity, on the animist drives that dwell in generative dark spaces of our artistic uncertainties? How do the aesthetics of encounter in this poem call me to dismantle something my heart knows? The word love does not fill me with aesthetic pleasure the way, say, decay does, with its simultaneous stiffening and softening, flesh giving way to pungent odors, to fluids that spill over any attempt at clean articulations. Love as a word feels somatically neutral, a space held abstractly for something more quivering and alive to move in. Dissolve, decompose—give me a word that flares my nostrils and makes me swallow hard.

I have previously written about love ecologically, offering a way to language the atmospheric sweep of affective assemblages of emotion and sensation formulating bodies into bio-metaphysical intelligences that exceed human intention. I have sought, in my art practice, to give bodies to the processes that the language of modernity reduces to metaphor, to let the erotics of the unknown unmake bodies into swarms of becomings and emergences, into fleshy refusals to be known or named, tickling and chaffing the haptics of vision with their strange familiarities.

I have no particular interest, however, in writing about or making art about love as a human enterprise. Maybe this is because that enterprise has failed to hold me in the kind of embrace I hear about in songs and stories. Maybe it is because those songs and stories often constrict the boundaries of my body into something lonelier and less teaming with microbes making love and symbiotic exchanges between the so-called insides and outsides of me. Maybe it is because I feel left out of the whole business altogether, the disappointments and revelations that unfold through intimate agreements that span decades. What marriage can this body of meadows and microplastics, dead stars, synaptic space and gut bacteria break through, and what will come to meet us?

But aren’t I already wading mouth deep in love? How else could the world do its grieving through me? Love, in this poem, doesn’t conquer all. It isn’t transcendent. It is a god forsaking immortality to experience organ failure and festering wounds. And what poem about love isn’t formed around a shape called death?

The longing that pours out of my open mouth could flood the village and Pittsburg. And however deep my desire is to be met with another set of teeth, tongue and lips licking, probing chewing through my heart pulsing in the muck of garbage, I know that no one really sleeps alone. We are enfolded in embraces that shape our bodies and stretch us beyond all the time our thoughts can hold. What eros is deeper than to die and be put into the earth forever? What love-work isn’t grief-work?

As my work as an artist continues to unfold in collaborative conversations on the breakdown of modernist myths of progress and human exceptionalism, and the risk required to meet the myriad challenges of these times, I often sit with the question: what affections must I get beyond? This isn’t an unfamiliar question in creative practice. Kill your darlings. Let go of the village. Learn to see how Pittsburgh is more than Pittsburgh. But there’s a bigger ask embedded in this moment traveling alongside an unfolding awareness that affections are often imbricated within systems that perpetuate inequalities, environmental destruction, resource hoarding, and violent conflicts. What if our affections are for a version of justice that affirms our entitlement to forms of safety that are unsustainable within the fraught social-ecological metabolism of the planet? What if our affections are for hope tied to the promise that we, humans, can save the world?

Love is not enough.

What should we insist on while there’s still time?

My prayer is to be brave enough to eat through wild hope to find the body that reeks within that body.

Whose sweet body is in your bed? What wildness will come for each of us when we tear it all down?